New research confirms that exercise can inhibit tumor growth by altering how the body processes glucose, favoring muscle cells over cancer cells. This finding, demonstrated in mice, suggests a similar effect may occur in humans, offering another compelling reason to prioritize physical activity.

The Metabolic Shift

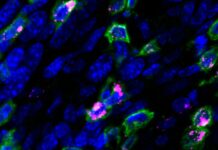

A study led by Rachel Perry at Yale School of Medicine reveals that exercise reshapes metabolic competition within the body. When mice with induced obesity were given access to exercise wheels, those who ran voluntarily developed tumors 60% smaller than those who remained sedentary. This reduction in tumor size correlated with increased glucose and oxygen uptake in muscle tissue and decreased uptake within the tumors themselves.

The key appears to be a fundamental shift in metabolic pathways. Exercise prompts changes in 417 genes related to metabolism, making muscle cells more efficient at utilizing glucose while simultaneously limiting glucose availability for cancer cells. Specifically, the protein mTOR, vital for cancer cell growth, was downregulated in tumors of exercising mice.

Why This Matters

The link between exercise and cancer survival is well-established, but the underlying mechanisms have been unclear. This study suggests a direct metabolic explanation: exercise creates a more competitive environment where cancer cells are starved of essential fuel.

“This work reveals that aerobic fitness fundamentally reshapes metabolic competition between muscle and tumors,” says Perry.

The implications extend beyond obesity, as similar metabolic changes have been observed in humans undergoing cancer treatment while exercising. This suggests that exercise could be a critical adjunct therapy, not just a lifestyle benefit.

The Bigger Picture

The study underscores the importance of muscle mass in cancer prevention. Individuals with lower muscle mass may be at higher risk of cancer death because their bodies have less capacity to prioritize glucose uptake in muscle tissue. Experts suggest that resistance training, alongside cardiovascular exercise, could be particularly beneficial for patients with low muscle mass.

The Next Steps

While the results are promising, researchers emphasize the need for clinical trials in humans. However, Rob Newton at Edith Cowan University states, “I really can’t see any reason why you wouldn’t have a similar effect in humans.”

The findings also raise the possibility that metabolic alterations may be a missing link connecting exercise, the gut microbiome, and the immune system in influencing tumor growth. Perry acknowledges that the benefits of exercise likely stem from multiple interacting mechanisms, not just one single pathway.

Ultimately, this research strengthens the case for viewing exercise as a powerful cancer-fighting tool, rather than merely a healthy habit.