Fossil evidence confirms that four-meter-long pythons thrived on the island of Taiwan during the Middle Pleistocene epoch, roughly 800,000 to 400,000 years ago. This discovery marks the first confirmed fossil record of pythons on Taiwan’s main island, challenging the current understanding of the region’s prehistoric fauna.

The Fossil Discovery

Paleontologists from National Taiwan University analyzed a remarkably well-preserved trunk vertebra unearthed near Tainan City. The specimen’s dimensions, reconstructed through 3D modeling, indicate a snake exceeding the size of any living Taiwanese reptile today. The fossil represents the largest snake ever found in Taiwan, hinting at a dramatically different ecosystem than the one present now.

Python Distribution Today

Modern pythons are found across tropical and subtropical Asia, Africa, and Australia. They range from Bangladesh and India to Indonesia, the Philippines, and parts of Africa south of the Sahara. Notably, no native pythons currently live on Taiwan itself. This makes the prehistoric presence of such a large python even more striking.

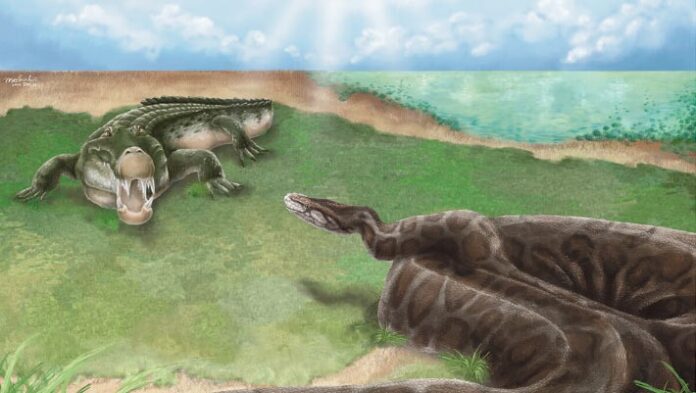

A Lost Ecosystem

The discovery isn’t isolated. The Chiting Formation, where the vertebra was found, has also yielded fossils of saber-toothed cats, giant crocodiles, mammoths, and extinct rhinoceroses. This assemblage points to a once-complex and predator-dominated ecosystem.

The researchers note that the extinction of these megafauna — including the giant python — created a significant ecological shift. The absence of such apex predators in Taiwan’s modern ecosystem suggests a vacant niche, potentially influencing the evolution of contemporary biodiversity.

Implications for Biodiversity

The fossil findings raise questions about the origins of Taiwan’s current animal life. The drastic change in the island’s fauna since the Pleistocene suggests a major ecological turnover. Further research is needed to fully understand how these ancient ecosystems influenced modern biodiversity in East Asia.

“The vanished top predator…indicates a drastic faunal turnover,” the scientists concluded, implying that the current ecosystem may still be recovering from a significant prehistoric loss.

The research was published in Historical Biology on January 16, 2026.