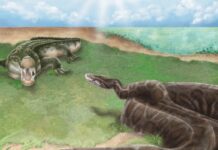

Paleontologists have discovered traces of chitin, a remarkably resilient organic polymer, within a 514.5 to 506.5 million-year-old trilobite fossil unearthed in California. This finding not only extends the known lifespan of preserved organic material in the fossil record but also suggests that sedimentary rocks may play a larger-than-appreciated role in long-term carbon storage.

The Discovery and Its Significance

The fossil, belonging to the Olenellus species, was analyzed using advanced fluorescent staining and spectroscopy techniques. Researchers led by Dr. Elizabeth Bailey from the University of Texas at San Antonio detected spectral signatures indicative of d-glucosamine, the building block of chitin. This discovery is noteworthy because chitin is the second most abundant organic polymer on Earth, following only cellulose.

Previous studies often failed to detect chitin in fossils, but modern analytical methods and this new research suggest that chitin can survive for hundreds of millions of years under the right conditions.

Why This Matters: Carbon Storage and Climate Implications

The persistence of chitin in ancient rocks has significant implications for understanding Earth’s carbon cycle. Limestones, common building materials formed from accumulated biological remains, often contain chitin-bearing organisms. The research suggests that these rocks contribute to long-term carbon sequestration, a process where carbon is locked away for geological timescales.

“When people think about carbon sequestration, they tend to think about trees,” Dr. Bailey explains. “But after cellulose, chitin is considered Earth’s second most abundant naturally occurring polymer.”

This insight challenges the prevailing focus on trees as the primary means of carbon capture. It indicates that geological formations, particularly sedimentary rocks, may represent a substantial reservoir of stored carbon. Understanding how organic matter survives in these settings is crucial for reconstructing Earth’s carbon history and projecting future climate changes.

Future Research and Implications

Though the study focused on a limited number of fossils, the findings suggest that chitin preservation may be more widespread than previously believed. Further research into the mechanisms of chitin survival in different geological contexts will be essential to refine our understanding of Earth’s carbon budget.

The research was published in December 2025 in the journal PALAIOS.

This discovery underscores the importance of reevaluating how we assess long-term carbon storage on Earth, recognizing that the planet’s crust holds vast reserves locked within ancient sedimentary formations.